I love alternate tunings. As a kid, I learned to play folk guitar, and I’d experimented a little with a couple of the more common “open tunings” used for bottleneck blues and such, I didn’t really get into deeply until I started listening to Joni Mitchell. She kind of blew my mind.

Much later as I got more serious about keyboards, and started learning to program synthesizers, I thought: “What if you could do the same thing on keyboard?” Turns out that open-tunings on a keyboard is a thing. And, it’s easy if you have more than one oscillator.

It’s a simple, but deceptively powerful harmonic trick: the “fifths patch”. These are patches where two oscillators are tuned in fifths – or a fourth below which is effectively the same thing. This creates an automatic shadow or parallel harmony that’s surprisingly interesting. For musicians, especially those dabbling in synthesis and MIDI, understanding this can open up a world of harmonic possibilities.

There have been numerous recordings written with fifths patches, which exhibit interesting harmonies and showcase the technique’s compositional power. Two striking examples of fifths patches in the wild are Bruce Woolley’s beautiful opening chords on Grace Jones’s “Slave to the Rhythm” and the complex harmonies in Weather Report’s “River People” from the album “Mr. Gone”. I’ve used them myself on a number of records – most notably the gated chords that provide the rhythmic hook on Shannon’s “Let The Music Play“.

These fifths patches, where oscillators are tuned in perfect intervals, not only create magical harmonies, but also offer a playground for musical exploration.

Play a single note on a keyboard set with a fifths patch, and you get a parallel fifth. Nothing clashes, but there’s nothing particularly interesting yet. But, as I discovered in my years as a session musician, the magic happens when you start exploring other intervals.

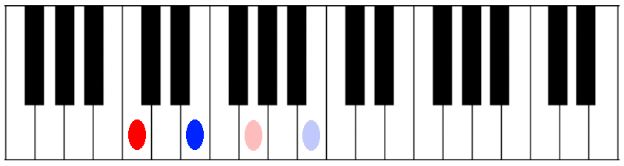

For example, if I play C and E, I hear C, E, plus their “synthetic harmony” at G, and B – a beautiful major seventh chord. This logic applies to all two-note intervals except the tritone and the minor second.

Triad Clusters

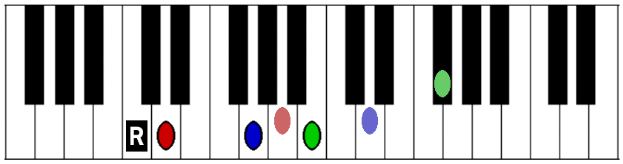

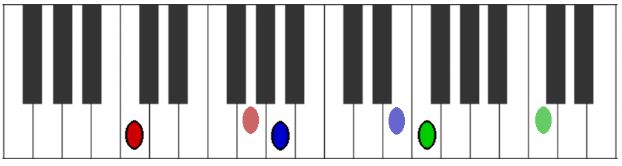

But why stop there?. Moving to three-note chords, you’ll find yourself crafting lovely six-note clusters. As long as these chords avoid the tricky tritone and minor second intervals, the harmonies you’ll get are nothing short of beautiful.Over time, I’ve learned to appreciate how these patches add inner harmonies and upper extensions to simple voicings.

Experimentation is key

Take, for instance, a simple G triad played over C. This major seventh sonority undergoes a kind of lydian transformation as the B (the major seventh) is shadowed by an F# (the fifth above B), resulting in a C6 add9 +11. The simple rule of thumb is: all intervals work EXCEPT the tritone, and the minor 2nd. It’s these extended harmonies that make fifths patches such a wonderful tool for exploration and composition.

Open voicings and drop 2s work nicely too since they’re built on consonant intervals. It takes a bit of practice to get used to what works and what doesn’t. The main thing is to stick to simple triadic voicings and avoid those tritones. Have fun.